Is Sisi the Solution?

April 17, 2014

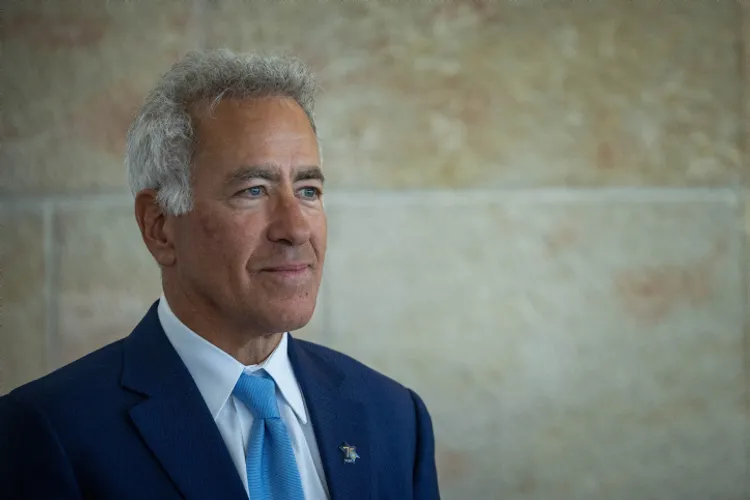

Here is an excerpt of a commentary by Prof. Yoram Meital, chairman of the Chaim Herzog Center for Middle East Studies and Diplomacy at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

The Jerusalem Report — The domestic power struggles in Egypt over the past three years can be likened to a series of gigantic waves, each one reshaping the country anew.

The first wave came in the form of a civil rebellion in January 2011, which culminated in the ouster of Hosni Mubarak 18 days later.

The second was driven by widespread opposition to the subsequent takeover by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.

The third saw the free election of the Islamist candidate Mohammed Morsi as president in June 2012, and his overthrow within the space of just over a year.

The direct intervention of the army and the security agencies in the conduct of the nation’s affairs and the presidential bid by Field Marshal Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, now a civilian, marks the beginning of the fourth wave. Given this volatility, the possibility of yet another wave washing over the country cannot be ruled out.

The historical starting point for an understanding of the current struggle is the Free Officers’ Revolution of July 1952. After they overthrew the monarchy, the officers laid the foundations for an authoritarian regime based on the military and the long arm of the internal security agencies. It consolidated its hold on power under presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak.

In January 2011, two slogans reverberated across Cairo’s Tahrir Square. The first, that “the people want the fall of the president,” was achieved in a heroic 18-day struggleby civil society in which about 800 protesters lost their lives. The second, that “the people want the fall of the regime” has yet to be achieved.

This resounding failure led to deep disillusionment over the chances of achieving significant change in Egypt. It was largely the result of the residual predominance of the military and the security agencies, and the moves on political power made by their leaders. But it is not simply more of the same. The uprising instilled in tens of millions of Egyptians a new political consciousness, the essence of which is profound resistance to a return to the old-style authoritarian regime.

Few in Egypt had heard of General al-Sisi before then-president Morsi appointed him defense minister and chief of the armed forces. The change in the upper echelons of the military was meant to strengthen Morsi’s hand and that of his main support base, the Islamist Muslim Brothers.

It was backed up by dozens of appointments of Morsi cronies to senior positions, the transfer of sweeping powers to the president and crude presidential intervention in the drafting of a new constitution. These moves triggered widespread opposition to Morsi and the Muslim Brothers, primarily from civil society groups, the security agencies and the army.

Millions of Egyptians joined the campaign for new presidential elections. There was an atmosphere of impending confrontation, threatening to spill over into violent clashes between supporters and opponents of the president. At this critical juncture, Sisi made his move, forcing the elected president Morsi out of office and publishing a controversial road map for solving the crisis.

This dramatic move marked the beginning of the fourth wave of the revolution that began in January 2011. The 59-year-old Sisi, who in the meantime had been promoted to field marshall, emerged as a leader who does not flinch from taking harsh measures against his opponents.

Sisi’s iron-fist policy won wide support from the “liberal” camp and among groups identified with the Mubarak regime. However, civil society activists identified with the January Revolution against Mubarak sounded loud warnings against the return of the police state.

But their attempts to rekindle a significant protest movement were aggressively crushed. Hundreds of civilians were killed and thousands arrested in clashes with the armed forces. Testimonies on human-rights violations and widespread use of torture appeared on a daily basis.

The fourth wave has also seen significant changes in Egypt’s foreign relations and national security policy. Most dramatically, Sisi made a 180 degree turnaround in Egyptian policy towards Hamas, a Palestinian offshoot of the Muslim Brothers. Whereas Morsi had been strongly supportive of the Gaza-based sister organization, the new military regime accused Hamas of interference in Egypt’s internal affairs and of aiding and abetting terrorist groups in Sinai.

Morsi’s overthrow and the return of the generals was received with open joy in Jerusalem. Israel was naturally delighted at the change in Egypt’s position on Hamas and the resolute action of its armed forces against militant groups in Sinai.

The Israeli-Egyptian security dialogue was significantly upgraded, and Israel agreed to an appreciable increase in the size of Egyptian forces in areas of Sinai that under the peace treaty are supposed to be demilitarized. Moreover, Israeli officials worked through diplomatic and PR channels to mitigate international criticism of the radical steps taken by the new Egyptian leadership.

In current circumstances, a Sisi victory in the forthcoming presidential election will not come as a big surprise. His supporters hope to curb the vicious cycle of violence and instability. The wide-ranging powers the new constitution confers on the president and the security forces could help the field marshal-cum-president impose law and order.

But civilian support for Sisi and the army’s continued involvement in the affairs of state is tenuous and could prove fleeting. The January Revolution created a significant change in political consciousness, especially among the young. Many oppose restoration of the authoritarian regime and see in Sisi a new potentially dictatorial pharaoh.

Read the full article from the April 21,2014 issue of The Jerusalem Report >>