Where Preservation and Growth Coexist

Where Preservation and Growth Coexist

February 2, 2015

Desert & Water Research, Negev Development & Community Programs

Baltimore Jewish Times — David Ben-Gurion’s vision was to make the Negev desert bloom, but Israel’s efforts to develop the arid lands of its southern interior often pit environmentalists against government land officials, and native Bedouin tribes against an influx of immigrants and longtime Israeli urban-dwellers.

Only 8 percent of Israel’s population lives in the vast Negev region, an area that comprises about 60 percent of the nation’s landmass.

Agriculturally, the country can produce about 45 percent of its calories, while the larger percentage of food is imported, says Prof. Alon Tal, of BGU’s Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research.

Prof. Tal thinks Israel could do better — such as by growing food in the Negev.

Wadi Attir, a unique sustainable agriculture project that addresses Prof. Tal’s urging, recently celebrated its inauguration ceremony in the Bedouin village of Hura, north of Beer-Sheva.

Initiated at the end of 2007 and estimated to be a $10 million project once fully realized, it is a collaboration of Dr. Michael Ben-Eli’s New York-based Sustainability Laboratory and Hura Mayor Dr. Mohammed Alnabari.

Dr. Ben-Eli, a 20-year veteran of sustainability research and advocacy, found himself drawn to the region’s 180,000 Bedouin residents during a visit to BGU’s Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research.

Interested in applying sustainability practices to help improve Bedouin living conditions, Dr. Ben-Eli met with Dr. Alnabari and others in Hura on a subsequent trip as well as researchers at BGU. Seed funding from private donors, including the Arnow family of New York, allowed them to proceed with this sustainable agriculture project in the Bedouin village.

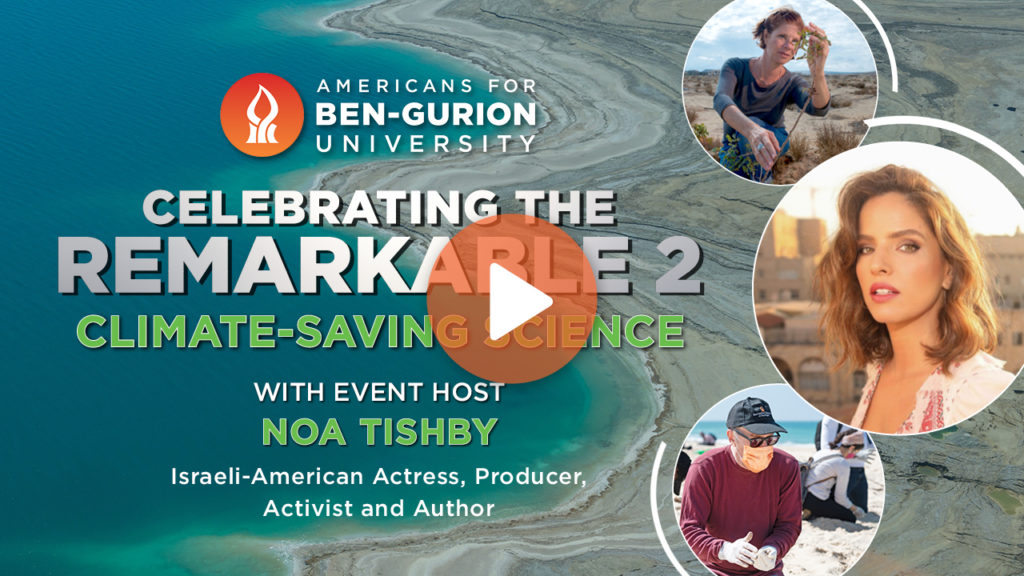

Dr. Michael Ben-Eli of Sustainability Laboratories; Sigal Shaltiel-Halevy, director-general of Israel’s Ministry for the Development of the Negev and the Galilee; Dr. Muhammad El-Nabari, mayor of Hura; BGU President Prof. Rivka Carmi; M.K. Yair Shamir, Israel’s minister of agriculture and rural development; Sheikh Yusuf Al Asibi.

Wadi Attir fuses traditional Bedouin agricultural and husbandry practices with the pioneering and inventive agriculture methods presented by Dr. Ben-Eli’s team.

The Bedouin staff learns techniques for soil enhancement and water retention and can receive training for eventual employment. They maintain the herds and crops and produce dairy products, medicinal herbals and cosmetic goods.

Situated in a semi-arid region, the teams were charged with the sizable task of enriching the soil.

Dr. Stefan Leu, a scientist at the French Associates Institute for Agriculture and Biotechnology of Drylands at BGU’s Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, says in the Negev region “the soil productivity and fertility is about 10 times less than it could be.”

He is working to replenish it after its destruction “thousands of years ago by early settlers and passing armies. The problem is the restoration of this vegetation; getting it all back is a very slow process.”

Echoing Bedouin farming practices, Leu recommended planting native trees such as olive, acacia, pistachio and carob that are useful as food as well as anchoring and nourishing the soil.

Dr. Leu devised systems of augmenting the landscape with natural rain catches made of small earth mounds and also overlaying the soil with leaves and straw, all of which capture water and prevent it from being washed into gullies or ravines.

To date, staff at Wadi Attir has planted 3,500 olive trees, constructed animal pens for their goat and sheep herds and built a large barn. There is also a sophisticated combination solar and wind energy system that heats up stored power to augment its energy output.

Plans include a visitors’ center, a milking facility, dairy operation and technology to convert waste into an energy resource. Ultimately, Dr. Ben-Eli says, the desire is to replicate the project in other desert regions around the world.