The Forgotten Legacy of 20th Century Pandemics

The Forgotten Legacy of 20th Century Pandemics

August 13, 2020

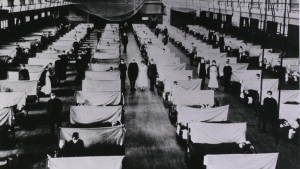

Scientific American (Excerpt) — The legacy of the 20th century’s deadliest pandemic shows how large groups remember—and forget—their shared past.

In 1924, Encyclopædia Britannica published a two-volume history of the 20th century thus far. But the book’s sprawling 1,300 pages never mention the catastrophic influenza pandemic that had killed between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide only five years earlier.

And many history textbooks in subsequent decades just note the 1918–1919 flu pandemic (often referred to as the “Spanish flu” because of mistaken beliefs about its origin) as an aside when discussing World War I, if at all.

Until quite recently, the pandemic had remained strangely faint in the public sphere, compared with other momentous events of the 20th century.

Of course, the pandemic was not forgotten entirely: many today are aware it occurred or even know of ancestors who succumbed to it.

But the event seems to form a disproportionately small part of our society’s narrative of its past.

That such a devastating pandemic could become so dormant in our collective memory puzzled Prof. Guy Beiner, of BGU’s Department of General History at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, prompting him to spend decades researching its legacy.

“We have an illusion. We believe that if an event is historically significant—if it affects many, many people, if it changes the fate of countries in the world, if many people die from it—then it will inevitably be remembered,” says Prof. Beiner. “That’s not at all how it works. And the Spanish flu is exactly a warning for that.”

Prof. Beiner began collecting books about the 1918 pandemic 20 years ago. For a long time, they emerged in a very slow trickle.

But now, as the world reckons with COVID-19, he can hardly keep up with the outpouring of both nonfiction and fiction. “I have, in my office, three stacks [of novels] waiting for me—huge stacks,” says Prof. Beiner.

Previously a niche topic even among historians, the 1918 flu has been compared to the current pandemic in terms of the fatality rate, apparent effectiveness of masks and social distancing, and potential economic impact.

In March 2020 alone, the English-language Wikipedia page for “Spanish flu” garnered more than 8.2 million views, shattering the pre-2020 monthly record of 144,000 views during the pandemic’s 2018 centennial.

The worldwide “forgetting” and ongoing rediscovery of the 1918 flu provide a window into the science of collective memory. And they offer tantalizing clues about how future generations might regard the current coronavirus pandemic.

For the countries engaged in World War I, the global conflict provided a clear narrative arc, replete with heroes and villains, victories and defeats.

From this standpoint, an invisible enemy such as the 1918 flu made little narrative sense. It had no clear origin, killed otherwise healthy people in multiple waves and slinked away without being understood.

Scientists at the time did not even know that a virus, not a bacterium, caused the flu. “The doctors had shame,” Prof. Beiner says. “It was a huge failure of modern medicine.” Without a narrative schema to anchor it, the pandemic all but vanished from public discourse soon after it ended.

Unlike the 1918 flu, so far COVID-19 has no massive war with which to compete in memory.

This year is not the first time a new pandemic has prompted reexamination of the one in 1918. The 20th century saw two more flu pandemics, which occurred in 1957 and 1968.

In both cases, “suddenly the memory of the Great Flu reoccurs,” Prof. Beiner says. “People begin looking for this precedent; people begin looking for the cure.”

Likewise, during the avian flu scare in 2005 and the swine flu pandemic in 2009, Google searches worldwide for “Spanish flu” spiked (though both increases were dwarfed by the one that occurred this past March).

All the while a growing body of historical research has been fleshing out the story of the 1918 flu, providing the foundation for a significant resurgence of its memory in the public sphere.

Prof. Beiner sees the current crisis as a tipping point in how society will remember the 1918 pandemic.

Among his collection of books about it, he says, “none of them became the big novel, a book which everybody is reading. I think this might change now.”

Prof. Beiner predicts COVID-19 will inspire a best-selling novel or major film centered on the flu of 1918. This type of cultural landmark could serve as an anchor for public discourse about the event, fortifying the present wave of social remembering.

As for COVID-19, Prof. Beiner anticipates similar “surges in memory and then lapses in memory” over the coming decades. “We’re going to have a complicated story. And it’s going to always be a dialectic, dynamic forgetting and remembering working together—what happens in the public sphere and what’s relegated to the private sphere,” he says.

A stronger collective memory of the 1918 flu could also help create the narrative schema necessary to maintain COVID-19’s public profile after today’s pandemic ends.