NYTimes: Israeli Vineyards in Negev are the Future of Winemaking

NYTimes: Israeli Vineyards in Negev are the Future of Winemaking

September 7, 2022

Desert & Water Research, Negev Development & Community Programs, Sustainability & Climate Change

The New York Times — As vintners around the world battle extreme heat and climate change, the pioneers producing wine in Israel’s arid south are testing ideas that might soon find global application.

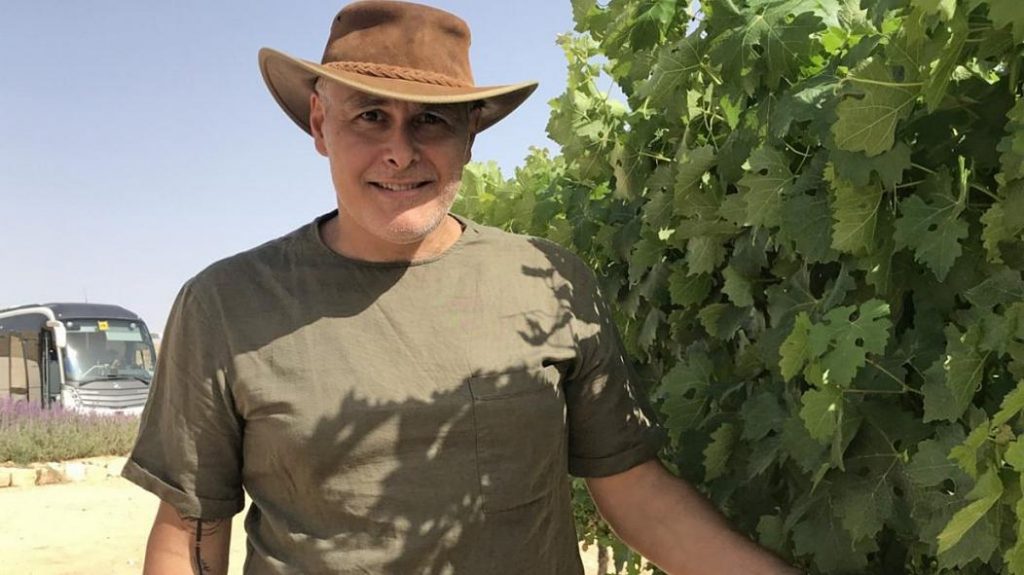

The global wine industry that must adapt to climate change, Israel could be a role model, said Prof. Aaron Fait, an expert in desert research and agriculture at The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. “The wine industry needs to understand that things are not as they were,” he said.

Prof. Aaron Fait of the French Associates Institute for Agriculture and Biotechnology of Drylands at BGU’s Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research

Say “wine tasting,” and the words immediately conjure images of verdant hills in Napa Valley or Tuscany. What they don’t bring to mind: the desert. But at a small cafe on a communal farm in the Negev Desert in southern Israel, a local winemaker was pouring a variety of deep crimson nectars last month, inviting some guests to swirl their glasses to release the fruity flavors and aromas. And the work is being done in the Negev, home to hundreds of technology start-ups and a futuristic solar tower — and long a laboratory for experimentation in Israel.

“It is in the Negev that the creativity and pioneering vigor of Israel shall be tested,” an iconic quote from David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founding prime minister, who lived out his last years about 50 yards away, in an austere wooden cabin. About 40 boutique wineries are scattered throughout the Negev, their emerald-green vineyards dotting the stark beige landscape. Still, even Ben-Gurion probably could not have imagined the unexpected scene at the cafe, whose shelves were stacked with bottles of locally produced malbec, merlot and petit verdot syrah.

But the climate then was probably more forgiving than it is now, and the area’s wineries are developing farming techniques that might soon need to be replicated around the globe, as the effects of climate change worsen. “To succeed in the Negev, you have to be bold and experiment,” said David Pinto, a vintner who planted his family plot with vines about three years ago.

With some 325 days of sunshine and little annual rainfall, the desert vines depend on drip irrigation, an innovation developed by another Negev collective in the 1960s that allows the farmer to tightly control the amount of water. Desert vineyards also come with some natural advantages. At night the temperatures drop steeply, even in midsummer, benefiting the vines. With low humidity, the Negev vines are exposed to few pests and fungi and require little pesticide spraying, making much of the wine production close to organic. While artificial irrigation is frowned upon in traditional winegrowing regions in Europe, and is even banned in some locales, it may become more of a necessity.

With some 325 days of sunshine and little annual rainfall, the desert vines depend on drip irrigation, an innovation developed by another Negev collective in the 1960s that allows the farmer to tightly control the amount of water. Desert vineyards also come with some natural advantages. At night the temperatures drop steeply, even in midsummer, benefiting the vines. With low humidity, the Negev vines are exposed to few pests and fungi and require little pesticide spraying, making much of the wine production close to organic. While artificial irrigation is frowned upon in traditional winegrowing regions in Europe, and is even banned in some locales, it may become more of a necessity.

Desert viniculture, and the tourists beginning to explore this relatively new wine route, have become important to the development and rebranding of the arid expanses that make up half the territory of Israel. While these Negev vineyards are new, making wine here is not. The area was famed for its locally produced wines in ancient times.

Among the ruins of Avdat, an ancient city in the Negev Highlands that existed from the Nabatean period in the fourth century B.C. until its demise soon after the Muslim conquest in the seventh century A.D., archaeologists have unearthed wine presses and cisterns from up to 1,600 years ago — evidence of a thriving Byzantine-era wine production and export industry.

Israeli researchers have identified at least two varieties of ancient seeds and are now trying to recreate the Byzantine white and red. “There are not many places in the world,” Mr. Shilo said, “that can boast 1,500 years of winemaking tradition.”