Fixing Fat Levels May Lower Risk of Autism

Fixing Fat Levels May Lower Risk of Autism

August 13, 2020

The Times of Israel — Children with autism appear to be more prone than others to a condition that skews lipid levels, BGU scientists find after crunching millions of medical records.

Abnormal levels of cholesterol and fats may be linked to autism in some cases, and adjusting them could prevent onset of the disorder, according to a major study by Israeli and American scientists published this week.

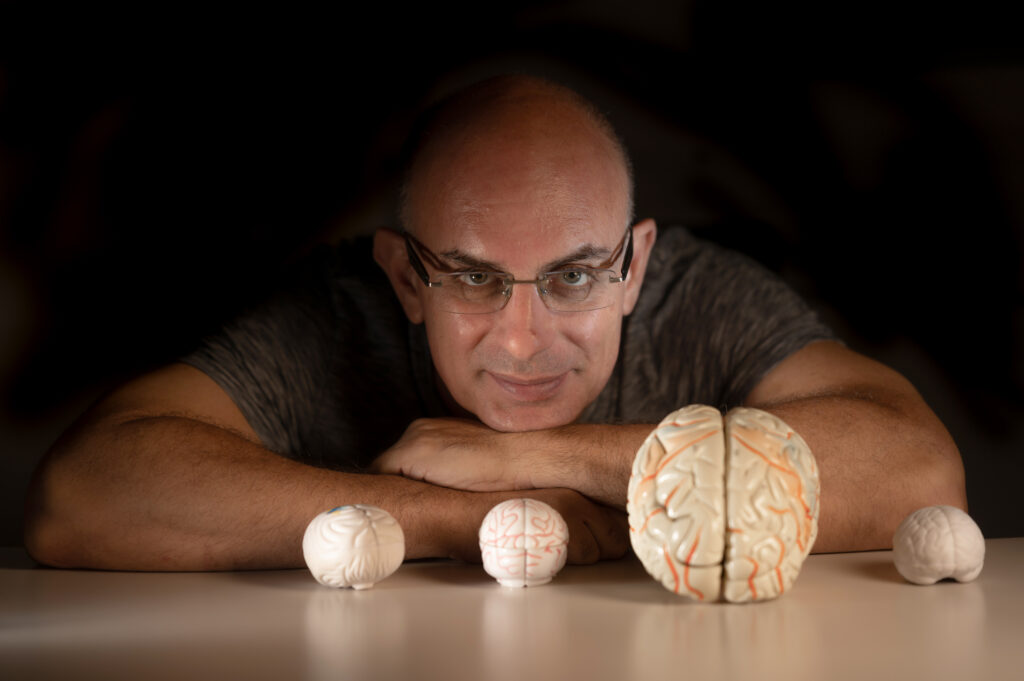

Dr. Alal Eran of BGU’s Center for Evolutionary Genomics and Medicine and Department of Life Sciences

The research team was led by Dr. Alal Eran, a computational biologist at BGU’s Center for Evolutionary Genomics and Medicine and Department of Life Sciences, and a member of the National Autism Research Center of Israel.

Dr. Eran is also a research associate at Boston Children’s Hospital, where she collaborated with scientists there and at Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Northwestern University for the newly peer-reviewed study, which was recently published in Nature Medicine.

The research team examined 2.75 million medical records at Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that children with autism are twice as likely than others to have dyslipidemia.

“The research may pave the way to preventing autism in some children by controlling their dyslipidemia, a condition that often goes undetected or untreated,” says Dr. Eran.

Dyslipidemia is characterized by irregular lipid levels, and is often caused by the body experiencing a genetically inherited difficulty in regulating them.

Blood lipids are fatty substances, such as cholesterol and triglycerides. Common irregularities in people with dyslipidemia include high levels of low-density lipoproteins, sometimes called bad cholesterol and/or low levels of high-density lipoproteins, which are sometimes called good cholesterol.

For now, the researchers have only managed to show a statistical link, and while further studies could point to a causal relationship, Dr. Eran cautioned that it is too early to recommend specific changes as a way to control or prevent autism.

“We’re not saying we’re going to change clinical practice tomorrow, but we are going to test whether using medication and controlling diet in a way that would push lipid levels within normal ranges could possibly impact behavior and lower the risk for autism,” says Dr. Eran.

The research does not suggest that autism is diet-induced, but rather that if dyslipidemia is present — ordinarily as an inherited condition — but managed well, it may avert autism symptoms.

“There is a very strong genetic background that predisposes people to dyslipidemia, and we are interested in the possibility that modulating this could impact the risk for autism,” she says.

The team found that 6% of children with autism have dyslipidemia compared to 3% of others. Though the percentages seem to be small, in the search to better understand autism this is a significant finding.

As well as exploring whether controlling dyslipidemia can affect the development of autism symptoms, Dr. Eran’s team is looking into the relevance of their new findings to diagnosis.

Autism is normally diagnosed based on behavior, at about three to four years old, and the genetic causes of most cases have not yet been identified.

But Dr. Eran says that her team’s findings can prompt careful monitoring of kids who have the condition for signs of autism. “The findings are exciting as they could lead to early detection.”

While the data leaves open the possibility that dyslipidemia just happens to occur more in children with autism than others, without a causative connection, Dr. Eran believes this is unlikely. “Our evidence suggests it’s not just a random association,” she says.

One observation that leads Dr. Eran in this direction is that her team found that mice with lipid irregularities similar to dyslipidemia have higher-than-normal incidence of unusual brain function. The research indicated that affected mice displayed learning difficulties.

But Dr. Eran stressed that practical recommendations based on the research would only be made, if justified, after controlled trials are conducted, meaning parents shouldn’t run off to start changing their children’s diets in the hope of reducing chances of autism.