Every Last Drop

May 3, 2016

J Weekly — Prof. Amit Gross of BGU’s Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research is a modern-day alchemist. But instead of turning lead into gold like a medieval sorcerer, Prof. Gross turns human waste into water — water pure enough to make the desert bloom.

“We need to treat waste as a resource,” says Prof. Gross, “and not as waste.”

From his Negev Desert base, Prof. Gross shows off a model biowaste recycler, which chugs away in the lobby of the Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research, where he teaches environmental engineering.

His machine resembles a high school science project gone wild. A biowaste digester filters human waste via natural processes, without chemicals. But it doesn’t stop there: The recycler also uses filters to trap toxic ammonia gas, ionizing it and folding it into a liquid that ultimately is suitable for irrigation.

Prof. Gross is one of many BGU scientists devoted to discovering advances in water technology. In a region that averages less than four inches of rain annually, nothing matters more than making every drop count, even if that drop originated in a toilet.

That’s a lesson Prof. Gross and his colleagues at BGU hope drought-plagued California can learn.

“The Western U.S. is using the knowledge accumulated here at universities and industry to solve water problems,” says Prof. Noam Weisbrod, director of the Zuckerberg Institute.

California’s $70 billion agriculture industry, as well as state and municipal government, turned to Israel for help. An Israeli-built desalination plant has opened near San Diego. And, Israeli water experts, including BGU academics from the Zuckerberg, have visited the state, advising on best practices when it comes to water conservation.

Conaway Ranch in California’s Yolo county recently announced that it has partnered with BGU and Netafim, Israel’s largest drip irrigation company, to develop a commercial rice crop that uses drip irrigation rather than conventional flood irrigation.

Given the demand agriculture places on California’s water supply, these are the kind of innovations needed in a state facing ever more water insecurity.

“We’ve outlined the testing procedures necessary to maximize success, based on experience growing a variety of crops in arid climates using subsurface drip irrigation,” says Prof. Eilon Adar, former director of the Zuckerberg Institute who was instrumental in this project geared toward reducing water consumption.

To make sure every drop counts, BGU researchers are also developing crops that can thrive on less water and tolerate brackish water.

Dr. Naftali Lazarovitch of BGU’s Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research deals in brackish water. He studies drip and saline-water irrigation, and also helps nearby farmers find ways to grow produce in the hottest, driest places on Earth.

He’s experimenting with a capillary barrier, in which a gravel layer is placed beneath the plant’s root zone. Adding sandy soils and volcanic ash gives higher yields, even in the desert.

Dr. Lazarovitch and his colleagues also use aeroponics to grow tomatoes without any soil at all — just a mixture of water and fertilizer placed in contact with the root.

One of BGU’s leading tomato experts is Dr. Aaron Fait, an Italian-born researcher who studies plant metabolic behavior at BGU’s French Associates Institute for Agriculture and Biotechnology of Drylands. He crossbred wild tomatoes with commercial varieties to create a product that tolerates the harsh Negev conditions.

He also has developed grape-growing techniques for the burgeoning wine industry in the Negev, where heat, salinity and sandy soil create challenging growing conditions. To conduct his studies, Dr. Fait established a living wine lab in Sde Boker.

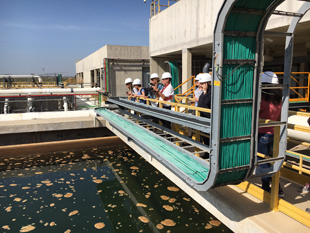

Observers watch seawater enter the first filtration tank at Sorek Desalination Plant. Photo: Dan Pine

Yet while recycled wastewater is perfect for agricultural use, it is not potable. For drinking water, Israel turns to the Mediterranean and desalinated seawater. Its newest desalination plant is the Sorek project, which opened its spigots in late 2013 and handles 20 percent of Israel’s municipal water demand.

To handle the volume, seawater is squeezed at high pressure through 16-inch cylindrical membranes, separating salts from H2O. A process known as biofouling, which causes algae and bacteria to form on those membranes, creates inefficiency and damage.

Prof. Moshe Herzberg of the Zuckerberg Institute studies biofouling and ways to circumvent it. The subject matters to him because, as he notes, “One billion people do not have access to clean drinking water,” and desalination, though expensive, is one of the best solutions, especially for dry regions like the Middle East. If we can prevent biofouling, he says, desalination would become less expensive.

In his lab, Prof. Herzberg has created membrane prototypes that resist biofouling. He even looked into designs that behave like the skin of jellyfish, which are not susceptible to bacteria growth. “We want to mimic nature,” he says.

Much of the time in Israel, however, nature can work against you. But to BGU botanist Prof. Jhonathan Ephrath, from the French Associates Institute, the country’s inhospitable terrain is a proving ground.

Wadi Mashash is the site of BGU’s experimental desert farm overseen by Prof. Ephrath and his graduate students. Unlike other agriculture sites across Israel, this one does not rely on drip irrigation.

Rather, it depends only on what falls from the sky, and the olive and acacia trees grown there were bred to thrive on minimal water.

“We have three to five rain events a year,” says Prof. Ephrath, a total of “about three inches. This runoff irrigation experiment is not for Israel, but to benefit the Third World.

“We do intensive agriculture for those without infrastructure,” he adds.

This post is excerpted from a cover story by Dan Pine, who participated in Americans for Ben-Gurion University’s 2016 Murray Fromson Media Mission.