Our Immune System Is Like a Feisty Invertebrate

Our Immune System Is Like a Feisty Invertebrate

December 7, 2018

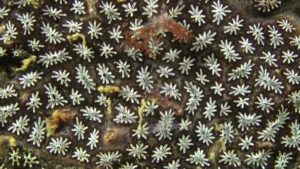

Science – The golden star tunicate may look like a flower, but this marine invertebrate is a brawler, attacking its tunicate neighbors in a ferocious cell-to-cell combat. Now, Ben-Gurion University scientists have discovered that the immune system of this pugnacious animal shows some unexpected similarities to our own. The finding could help uncover new approaches for preventing rejection of transplanted organs or treating cancer.

Tunicates are the closest living relatives of vertebrates—the group that includes humans, sharks, mice, and turtles—but the two evolutionary lines separated about 500 million years ago. The 3-millimeter-long, tube-shaped animals cluster in colonies on rocks and other hard underwater surfaces, fanning out like petals. When one growing colony contacts another, they have to decide “are they going to fight or are they going to fuse,” says study co-author Benyamin Rosental, a cellular immunologist now at BGU.

Tunicates are the closest living relatives of vertebrates—the group that includes humans, sharks, mice, and turtles—but the two evolutionary lines separated about 500 million years ago. The 3-millimeter-long, tube-shaped animals cluster in colonies on rocks and other hard underwater surfaces, fanning out like petals. When one growing colony contacts another, they have to decide “are they going to fight or are they going to fuse,” says study co-author Benyamin Rosental, a cellular immunologist now at BGU.

Unless both colonies carry the same version of a particular protein, they fight. Cells from the two colonies attack and destroy one another in battles akin to what happens when the human immune system rejects a transplanted organ.

To probe how the golden star tunicate’s immune system works, a team led by Rosental and bioinformatician Mark Kowarsky of Stanford University isolated 34 types of cells from the animal. They found some cells switched on the same genes that are active in our hematopoietic stem cells, the blood-forming cells that spawn all the cells of our immune system. Like vertebrate hematopoietic stem cells, the tunicate versions can divide and specialize into different cell types, the scientists determined.

Another way in which the tunicates’ immune system mirrors the vertebrate version involves cells that are specialized to kill other cells. In our bodies, these assassins include natural killer cells, which target tumor cells or cells infected by viruses. The scientists’ report in Nature magazine showed that tunicates also deploy such cell executioners.

When the researchers staged fights in the lab dish between cells from different tunicates, they found that the bodies piled up. Analyzing the genes that are active in these killer cells may help researchers pin down the crucial genes that spur organ rejection, says Rosental, and could suggest new ways to eliminate cancer cells.

Rosental and colleagues are now studying other invertebrates such as sea urchins to determine how much further back in evolutionary history these features extend.