Eichmann Trial Altered Worldview of Holocaust

May 2, 2011

Uncategorized

![]() In 1960, when Israel announced it had captured Adolf Eichmann and would try him for his role in the murder of 6 million Jews, attitudes in Western countries toward the “Final Solution” were very different from what they are today. Among non-Jews, the prevailing sentiment was one of indifference, much as it had been so consequentially in the years 1933-45.

In 1960, when Israel announced it had captured Adolf Eichmann and would try him for his role in the murder of 6 million Jews, attitudes in Western countries toward the “Final Solution” were very different from what they are today. Among non-Jews, the prevailing sentiment was one of indifference, much as it had been so consequentially in the years 1933-45.

Jews themselves also tended to avoid the subject. The memories were too painful, menacing, humiliating, to be acknowledged. As Judith Stern of Ben-Gurion University writes, the consensus among Jews then was that “Holocaust experiences were better left unexplored.”

These were the experiences, of course, that were to be confronted at Eichmann’s trial. The prospect aroused deep anxiety in many Jews. The day after the trial began, a Jerusalem newspaper published a cartoon showing Israel harried by ghosts: Its caption read “Worries, warnings, doubts.”

Yet there were also those who recognized the historical and existential significance of Eichmann’s capture and trial. Persecution, often genocidal, is a central and recurring theme in Jewish history. Never before, however, in all that long history of suffering, had Jews sat in judgment on one of their persecutors. Now, they would do so – in Jerusalem, ancient capital of their newly recovered sovereignty. Was this not proof of their bold emergence from the terrible darkness that had enveloped them?

As if in response to this militant new reality, Eichmann’s capture unleashed a global torrent of criticism. Israel was condemned in a U.N. Security Council resolution supported by the United States, Great Britain and France. According to the Anti-defamation League, 70 percent of American newspapers commenting on the capture did so unfavorably.

Particularly in Western Europe, criticism was often blatantly anti-Semitic. One of England’s most respected intellectuals, for example, described Israel’s seizure of Eichmann as “an act of tribal vengeance.”

Despite this ugly carping, the Eichmann trial brought about profoundly important changes. In the trial’s wake, the non-Jewish world became intensely (and, for the most part, sympathetically) aware of the Holocaust. Large numbers of books about the Holocaust were published, often enjoying immense sales. Movies and television programs were watched by huge audiences.

About sixty Holocaust museums were established around the world. And Auschwitz and other death camps attracted vast throngs of somber visitors. The destruction of European Jewry at last entered the world’s consciousness – and conscience.

For Jews, too, there was a profound change. “After the trial,” according to professor Hillel Klein, a specialist in the psychiatric treatment of Holocaust survivors, “it became possible (for Jews) to remember.”

The trial altered our relation to the Holocaust. Now, we were no longer just the victims but were also the prosecutors of those who had victimized us. In that enlarged role, it was necessary to face the facts we had avoided. And so, we did face them.

One must not overstate the catharsis offered by the trial. In the end, the calamity remains a calamity and the scars are only partly healed. (Holocaust survivors are over three times as likely to commit suicide than others their age.) But it became possible for us to acknowledge the memories and cope with them.

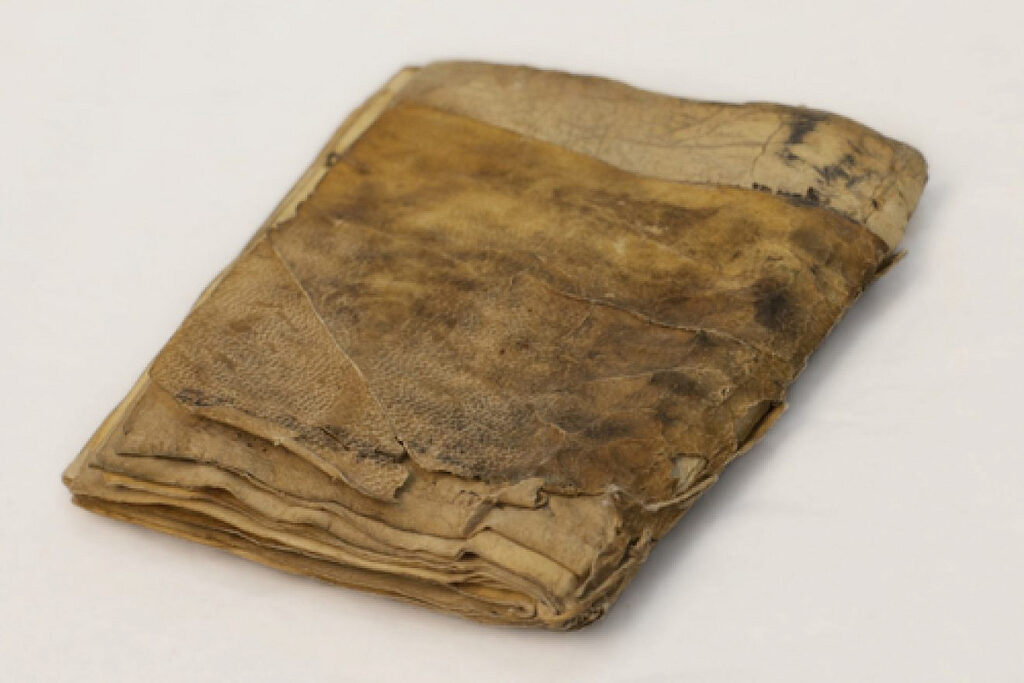

When Eichmann was captured, Israel’s official Holocaust memorial had been a “Hall of Remembrance” in Jerusalem. Inside, only a memorial flame and the names of some concentration camps inscribed on the floor evoked the tragedy. Consistent with the prevalent strategy of looking away, this was a place of remembrance that was almost devoid of memory.

That hall is now part of a large complex of memorial buildings. One commemorates a million murdered children. In another, researchers are still compiling the victims’ names. A vast museum is the centerpiece of this complex. In cruel detail, it documents the facts of the Holocaust.

Leaving the museum, one walks out onto a marble terrace. It overlooks a beautiful view of the Judean hills, on which newly built villages and townships now nestle among lush, still young, evergreen forests. The architecture’s symbolism is not subtle, but it is both heart-rending and heartening. It records the changes that have taken place in the soul of the Jewish people – which the capture and trial of Adolf Eichmann helped bring about.

Michael Selzer covered the first four weeks of the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem for the Oxford University undergraduate weekly Isis. He has lived in Arizona since 1999.