Drug Appears Safe for Morning Sickness

Drug Appears Safe for Morning Sickness

June 15, 2009

Medical Research, Social Sciences & Humanities

Morning sickness is an unavoidable part of pregnancy for most women, but many are reluctant to take medications to quell nausea and vomiting.

Morning sickness is an unavoidable part of pregnancy for most women, but many are reluctant to take medications to quell nausea and vomiting.

Now one of the largest studies ever done on a commonly used anti-nausea drug, metoclopramide, has concluded it is safe and does not affect fetal development, even when taken during the first trimester, a critical period of development.

The study, released Thursday in The New England Journal of Medicine, analyzed the outcomes of more than 80,000 births in southern Israel over the course of a decade. It found that the 3,458 babies whose mothers were prescribed the drug during the first trimester of pregnancy fared just as well as other babies.

They were no more likely to be born with congenital abnormalities or to have other problems, such as being born prematurely, having a low birth weight or dying, the study found.

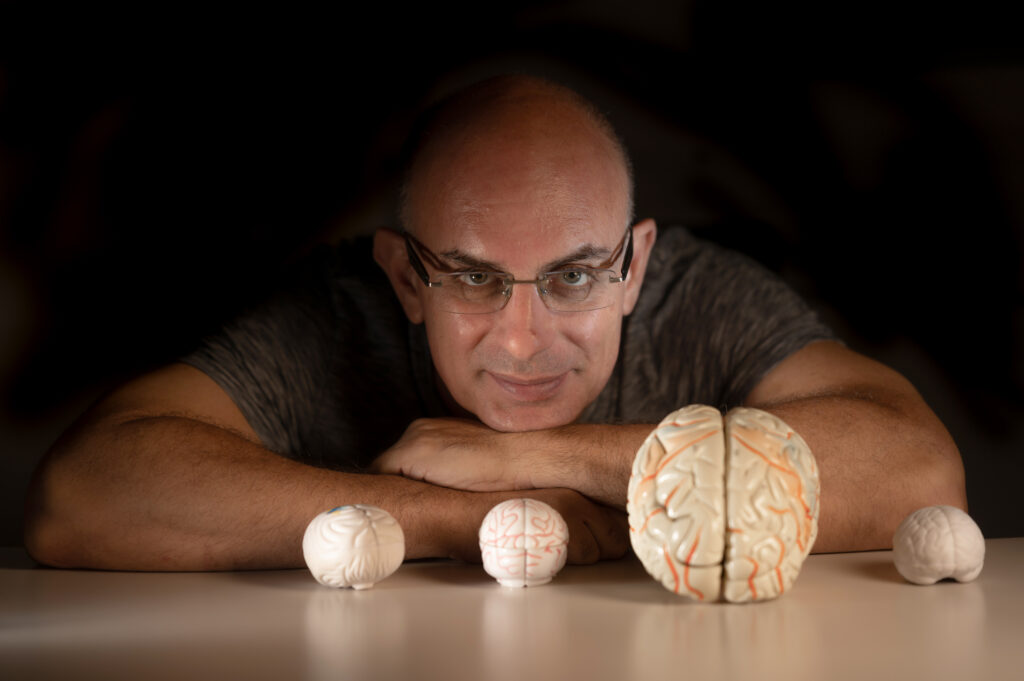

“Our study is about 10 times larger than all of the other studies of this drug put together,” said Dr. Rafael Gorodischer, one of the study’s authors and a professor emeritus of pediatrics at Ben-Gurion University in Israel.

“We studied exposure in the first trimester because that is the most critical period for the development of the fetus, when most malformations would be caused by an external cause.”

“We can now say with a high degree of confidence that it’s a safe medication,” he said.

Metoclopramide is already used to treat severe morning sickness in the United States, where it is commonly sold under the brand name Reglan. But while physicians who care for pregnant women said the results of the new study are reassuring, they said they weren’t likely to prescribe it for run-of-the-mill morning sickness of the kind most women experience at the beginning of pregnancy.

But while physicians who care for pregnant women said the results of the new study are reassuring, they said they weren’t likely to prescribe it for run-of-the-mill morning sickness of the kind most women experience at the beginning of pregnancy.

For women with mild nausea and vomiting once or twice a day, “There are conservative measures they can try, like eating little bits of food all the time so they always have something in their stomach, using antacids to deal with indigestion, or staying away from caffeine or anything that smells bad to them,” said Dr. Peter Bernstein, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York.

Still, Dr. Bernstein said the study was strong not just because of its size but because it weighed factors other than malformations, such as birth weight, that also affect the health of the baby.

To do the study, researchers analyzed a computerized database of all medications dispensed to women in a health plan in southern Israel from the start of 1998 to the end of March, 2007.

They linked that with maternal and infant hospital records during the same period of time, looking at associations between the use of metoclopramide and adverse outcomes in the babies.

Some 4.2 percent of the 81,703 babies born during the 10-year period were born to mothers who had been prescribed the drug, but researchers found they were not at increased risk for congenital abnormalities, prematurity, low birth weight or mortality soon after birth.

While some 5.3 percent of babies exposed to metoclopramide were born with birth defects, compared with 4.9 percent of those who had not been exposed to the drug, the difference was so small that it could easily have occurred by chance.

There were also no significant differences in the risk for low Apgar scores, a series of measures done immediately after birth to assess newborn health, the researchers found.

Most of the women were prescribed the equivalent of about a week’s worth of the medication, but researchers were unable to know for sure whether they actually took the drug or not. Additional calculations determined that even babies whose mothers took the drug for more than a week did not face increased risks.

Metoclopramide, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, is used to treat gastric problems, nausea and heartburn in adults. Long-term chronic use, however, is associated with tardive dyskinesia, a movement disorder.

It is considered a Category B drug, which means it is presumed to be safe to a fetus based on animal studies, though controlled studies of pregnant women have not been done. It is one of several drugs already used in the United States to treat severe nausea and vomiting during pregnancy.