Dogs That Can Smell Cancer

January 30, 2013

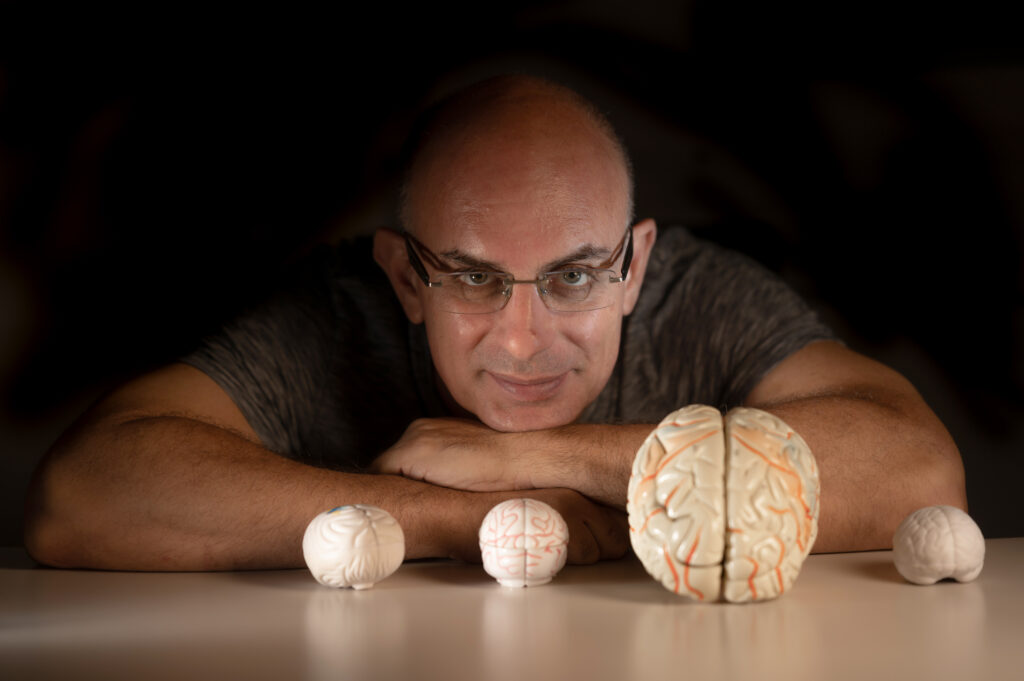

Dr. Uri Yoel, M.D., a 43-year-old specialist in internal medicine and instructor at the BGU Faculty of Health Sciences, conducts research on the ability of dogs to smell cancer. His finding: there is no doubt that dogs can differentiate the smell of cancer cells from non-cancerous cells in cell cultures.

This research project, like so many others, was born of serendipity. During Yoel’s residency at BGU, his advisor, Prof. Pesach Shvartzman, incumbent of the Mayman Chair in Family Medicine, invited him to join an investigation into dogs’ capacity to detect cancer. The project was the idea of a family friend, a dog trainer, eager to extend his subjects’ skills to beyond sniffing out drugs and explosives.

The idea of using the sniffing ability of dogs to detect cancerous cells first emerged a decade ago in an article in a medical journal about a woman who discovered she had melanoma when her dog repeatedly barked at her tumor. This set off a tidal wave of letters from readers who had had similar experiences.

“In the case of lung cancer or melanoma this did not come as a great surprise, as it made sense that the cancer could be smelled on the patient’s breath or skin. Regarding other forms of the disease, like breast cancer, it was less evident,” says Yoel. “All smells leave a molecular footprint, but with something like breast cancer it was hard to understand how this worked.”

Yoel volunteered to enter the project. First the two canine participants were taught to smell and detect cell cultures originating from malignant breast cancer and to differentiate them from non-cancerous cell cultures. When the dogs were ready they were tested for their ability to find one malignant cell culture plate located between four other non-cancerous cell culture plates.

The experiment raised fascinating questions. Do all cancers share a common smell or do different forms of the disease have distinct odors? Are the dogs detecting material from cancer cells themselves or the body’s reaction to the disease, in the form of necrosis or inflammation?

And while Yoel wanted the animals to give a total scan of all cancers, the dogs would identify one form and ignore another.

“We checked this with in vitro cell cultures of breast and lung cancer and melanoma. It was logical that if the dogs respond to cell cultures, they are reacting to the smell of the cancer itself,” says Yoel.

“The dogs were taught to smell only breast cancer cell cultures but were tested also for their ability to recognize lung cancer and melanoma cell cultures. They scored a perfect 100 percent in all cases.”

“Our research proves that dogs can smell cancer cells in vitro, and that different types of cancer share the same smell print,” says Yoel. “Again, we cannot know for sure if in vivo, the dogs are reacting to the cancer itself or to the body’s reaction to it. I think that the cancer itself has a special smell print that the animals detect, though it may be a combination of the two factors.”

The next step is to check the dogs’ reaction to people with cancer. Yoel will begin by training the dogs to identify lung cancer. To do this, he will expose them to hundreds of smokers to look for those with early stage disease.

However promising, this research is hindered by the fact that it is conducted solely by volunteers, including Yoel, who work in their free time. To take the project further, Yoel must employ two dog trainers for at least a year. He will also need to add another two dogs as backups in case one of the original two trained animals is unable to work. Further, he needs a permanent place in which to house the canines.

“Even before we start training the dogs, we must see if they are suitable for this type of work,” he says. “We need to see the dogs’ qualities as puppies and to trace their development. All this takes time – and modest resources.”

This compelling research and Yoel’s intensive work as an internist at Soroka University Medical Center are linked to his personal ethic, which centers on active connection to others. His private life is no less governed by the principle.

Yoel, his wife and five children live at Kfar Rafael, a community close to Beer-Sheva for adults with mental disabilities. The Yoels share their home with six mentally

disabled adults and Yoel’s wife Michal, oversees the group.

“I became an internist because it combines connection with people, the thought process of diagnosis, research and intensive care,” says Yoel. “And living at Kfar Rafael, you devote ‘more than a little’ time to others. This has made for a life filled with meaning.”