A New Look at the Negev Desert

September 16, 2009

Alternative Energy, Desert & Water Research, Medical Research, Negev Development & Community Programs

Israel gets a lot of attention. Much of it focuses on tenuous peace talks, missile crises, troubled government elections and internal religious strife. But that’s not all there is to Israel. Beyond the blaring headlines, ordinary life goes on.

But the southern region, starting at Beer-Sheva and going into the Negev Desert, is equally fascinating. On the recent Murray Fromson Media Mission, sponsored by the American Associates, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, that’s where 10 American journalists went. I was one of them.  Although it’s called a “desert,” there are no sand dunes. Moonscape is the word that comes to mind, but that’s not quite accurate. There are lots of rocks but also scrubby bushes and even an occasional patch of trees, deliberately planted to capture the sparse rainfall.

Although it’s called a “desert,” there are no sand dunes. Moonscape is the word that comes to mind, but that’s not quite accurate. There are lots of rocks but also scrubby bushes and even an occasional patch of trees, deliberately planted to capture the sparse rainfall.

What impressed me the most, though, is the spirit of the place. With 60 percent of the country’s land, but only 10 percent of its population, the Negev is a vast and open frontier.

This is a place for pioneers and for entrepreneurs who want to make their mark. On that note, here’s a look at life beyond the headlines.

Bedouin Health

In Israel, there are northern and southern Bedouin tribes. The ones in the industrialized north have melted into the Israeli Arab society. The ones in the south have not.

About 160,000 Bedouins live in the south. “Do they live in tents?” someone asks, a romanticized image of this once-nomadic people in mind. The reality is quite different.

Half have chosen to live in government “recognized” villages, where they get electricity, running water and schools. The other half live in their own villages, a word that hardly describes the clusters of shacks you glimpse by the side of the road or off in a distant field.

Men have more than one wife, typically two or three. Sixty-five percent marry first or second cousins. Each wife averages eight to nine children. By age 50, a man could have 300-plus grandchildren.

“They’re the fastest-growing population in the world,” says Dr. Ohad Birk, head of the Genetics Institute at Soroka University Medical Center and a member of Ben-Gurion University’s faculty of health sciences.

Dr. Birk, a short man with blond hair, studies genetic diseases among the largely inbred southern Bedouins. They do not carry more genetic mutations than the general population. But because of the age-old custom of tribal intermarriage, the odds of marrying someone with the same mutations increase.

A Bedouin tribe of 10,000 can have one to three diseases. The diseases are common to that tribe. Dr. Birk, for example, has found the gene for diabetes in tribes. Other diseases are not only rare but extremely severe.

In one, infants are born seemingly healthy, but by age 2 or 3 they take ill and by 8 or 9 they die. In another, children are born with eyelids but no eyes.

Soroka Hospital, located on the BGU campus, serves the entire Negev region. It has trained Bedouin maternity nurses to go into the villages and draw blood from pregnant women. If a suspect gene is found, the women are invited to the hospital for further testing and counseling.

Many are doing so. In four years, the number of genetic tests has quadrupled. As a result, infant mortality has dropped from 17 to 11 in 1,000 births. (By comparison, infant mortality in the U.S. is 4 in 1,000 births.)

Bedouins are a common sight at the hospital. The women wear floor-length skirts, long-sleeved tops and headscarves; the men, black jackets and pants. Despite their traditional garb, the modern world is changing their lives.

Dr. Birk says the older generation is aware of genetics and the younger Bedouin want to marry for love.

He has seen fathers bring their children to the hospital for testing for genetic diseases. A young couple came in for premarital testing. Both turned out to be carriers. “He still wanted to get married. She didn’t,” he says.

Every time Dr. Birk publishes another finding, he gets thousands of inquiries from around the world. Eventually, he hopes to develop a test for the most common genetic diseases among the Bedouin.

The test would be applicable beyond the southern Bedouin. They share the same genetic heritage as the Arabs in Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi. “And that,” he says, “is a huge population.”

Anchoring Masada

Yossi Hatzor looks like an Israeli Indiana Jones. He’s got a short grizzled beard and mustache. He’s wearing khaki pants and a rolled-up long-sleeve shirt.

A bright yellow backpack, baseball cap and sunglasses roped around his neck complete the look. Instead of a whip, he’s packing a pistol on his hip, as many Israelis casually do.

Mr. Hatzor points to a large “tension” crack on the Snake Path cliff, on the east side of Masada, just above where the old cable car used to be.

In the 1990s, when Masada, a national monument that was the last Jewish holdout against Romans in the revolt of 70 C.E., was being spiffed up for the growing number of tourists, a new, larger cable car was planned.

It turned out, though, that the old cable car’s location wasn’t so good. Looming above the path from the anchoring point to a proposed new bridge were two keyblocks, in the jargon, that had separated from the mountain’s surface.

The old cable car had been installed in the 1970s and, says Mr. Hatzor, a geology professor at BGU, “For 30 years, it was pure luck that a rock didn’t fall into the original cable car.”

The Masada authorities got nervous. When they looked, he says, they found other rocks that had separated from the cliff. That made them even more nervous because Masada is at the western end of the seismically active Dead Sea rift valley.

Mr. Hatzor, a specialist in rock mechanics, was called in to study the situation.

As a result, 30 anchor rods were installed in the two keyblocks, one 1,500 metric tons and the other 500 metric tons. The rods extend 60 feet into the base rock of Masada, but their ends bulged out. As camouflage, the ends were covered with painted plaster.

It’s only when Mr. Hatzor points them out that you notice they’re a slightly lighter beige color than the mountain itself.

The new cable car was installed in 1999 by a Swiss company with Israeli engineers. It has been placed near, but not in, the exact spot of the old cable car. The new 150-ton cable car is secured by six 100-ton anchors with 120-foot-long rods that, says Mr. Hatzor, “almost come out the other side of the mountain.”

While the vibrations of the cable car influenced the rock separation, it wasn’t the only factor and the east face wasn’t the only side that needed reinforcement. “You have displacement of rock over time,” says Mr. Hatzor. “A month ago, during the last rainstorm, a huge block collapsed, but it wasn’t in the path of visitors.”

Some stabilization has taken place on the north face, but loose rocks elsewhere that do not endanger visitors have been left as is. Interestingly, the flat top of Masada has remained remarkably stable over the past 2,000 years despite recurring earthquakes.

“We thought the issue was earthquakes, but it turned out to be climatic,” says Mr. Hatzor. “Masada will be here for a long time, but it’s a living structure. There is erosion and climate. It needs taking care of.”

“You know,” I tell Mr. Hatzor, “in the U.S. Rockies, they put black netting on rocks by the side of the highway that look like they could fall down. Have the Israeli authorities thought of doing that?” Black netting? On Masada? He gives me a horrified look. I take that as a “no.”

Safe And Secure

The horror of Sept. 11, 2001, happened in the United States. But the shock waves traveled far beyond. “It had an impact on worldwide security,” Doron Havazelet says of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. (A third plane crashed in a Pennsylvania field.)

Mr. Havazelet is an astrophysicist in BGU’s Department of Information Systems Engineering as well as a reserve officer in the Israel Defense Forces and a former senior official in the Ministry of Defense.

A year ago, Mr. Havazelet, a short stocky man dressed in a navy blue suit, came to BGU to found a new Institute of Homeland Security. He now heads the institute, which draws on 80 experts from five BGU faculties in an effort to provide an overall picture of the security situation.

In an afternoon devoted to the topic, experts discuss different aspects of that vast topic. One talks about cyber intelligence, in which software is being developed to search the Internet for terrorist-generated content and coded messages.

Another demonstrates intelligence gathering and security assessment through robotic technology. Via remote control, robots that resemble mechanical snakes and spiders relay images from the most inaccessible places.

In a third presentation, two experts talk about biosensors, which basically means a variety of deadly diseases, quick diagnosis and a “bioplan” to address. Some of their research is being funded by the U.S. Army and the U.S. State Department.

BGU’s Institute of Homeland Security is by no means the only such facility, either in Israel or elsewhere in the world. “A lot of money is available from governments, from corporations, to deal with it,” says Mr. Havazelet.

But homeland security raises a host of questions and he touches on a few, from the legality to the economics. If, in order to protect itself, a country adopts homeland security measures that are too restrictive, they end up harming the host.

“It’s a war between cultures,” says Mr. Havazelet. “You have to keep the Western world undamaged because that’s what [the terrorists] are after.”

Mr. Havazelet says the institute works on an international basis. It tries to go beyond reacting and get into the realm of predicting.

But institutes like BGU’s have their limits. Take, for example, the issue of financing terrorism. It would seem easy to follow the money that funds terrorist groups. Not so, he says. There are complications, and he gives Swiss banks as an example.

“A lot of money for the Swiss government comes from the banks, so the government isn’t doing anything about bank account secrecy,” says Mr. Havazelet.

As for the institute’s information collecting and data gathering, he says that if it found anything of interest to the U.S., it would be related to Israeli government officials who presumably would share it with their American counterparts.

What happens after that, though, is out of the institute’s control. “It’s up to the leaders,” says Mr. Havazelet. “If the leaders choose not to act, that’s the end of it.”

Wine Country

The Boker Valley Vineyards Farm is located between Mitzpe Ramon and Sde Boker. A modern oasis in the desert, there is a tented outdoor area with tables and chairs, guest lodges, green fields and, surprise, an invitingly cool and spacious restaurant/bar.

The Boker Valley Vineyards Farm is located between Mitzpe Ramon and Sde Boker. A modern oasis in the desert, there is a tented outdoor area with tables and chairs, guest lodges, green fields and, surprise, an invitingly cool and spacious restaurant/bar.

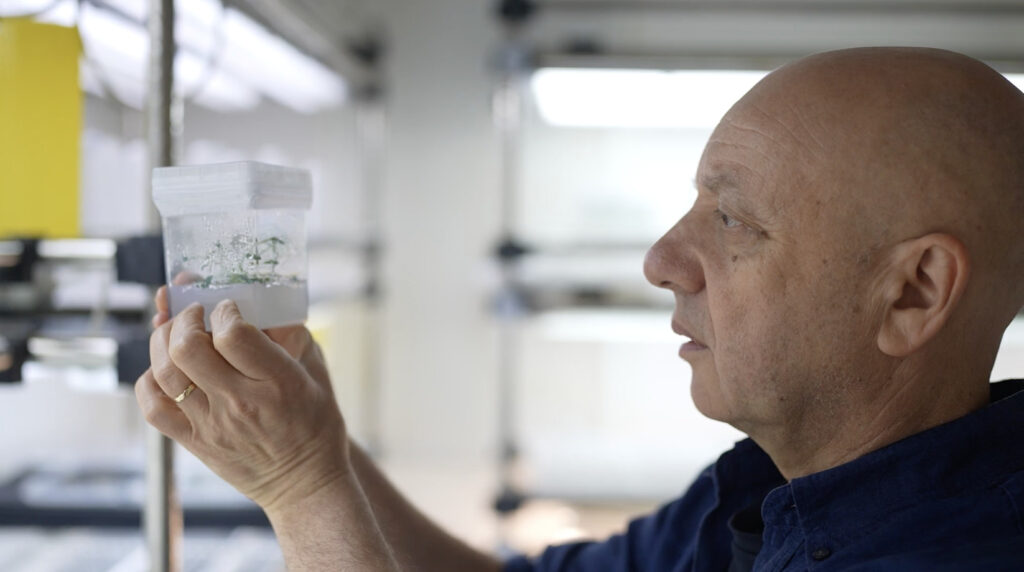

Zeev Wiesman is waiting for us. Tall and rugged, dressed casually in jeans and sports shirt, he doesn’t look like he spends his days in a laboratory. But that, indeed, is what he does and the result is a number of crops that now grow in the Negev’s harsh environment.

“I want to develop a sustainable industry,” says Mr. Wiesman, a professor in BGU’s Department of Biotechnology Engineering and head of its phyto-lipid biotech lab.

The Negev contains most of Israel’s land, but few plants can grow in the heat and dryness and salty water.

Mr. Wiesman’s experimental projects have produced hits and misses. Apples didn’t succeed.

They tolerated the heat, but not the lack of good-quality water. He did better with olive trees.

There are now 5,000 trees in olive plantations in the Negev, thanks to a unique irrigation technique his team developed.

“That’s 20-25 years of work,” he says of the olive trees. His latest project is a vineyard across the road from Valley Vineyards Farm.

There are 2,000 acres under cultivation. Moshe Zohar, a farmer “with a green thumb,” says Mr. Wiesman, tends the vineyard. A family man with three children, Mr. Zohar owns the Vineyards Farm; the vineyard itself is on government land.

“Everyone thought we were crazy,” Mr. Wiesman says of the vineyard. “They asked, ‘What are you doing planting grapes? There’s no rain.'”

Long ago, the area was known for its large wineries and he believed it could happen again. He admits, though, that it was a challenge to find a grape that would adapt to the environment. He also wanted a grape variety that met market demand.

There was a decade of experimenting, then the vineyard was planted. By Jewish law, he had to wait three years for the plants to mature. The grape harvesting began about five years ago.

The vines are strung on horizontal wires in orderly rows. In early spring, the vines are in a dormant stage, but soon they will be lush and green, ready to produce the cabernet sauvignon and merlot grapes for which they were planted.

Sweet water is pumped from the north, then mixed with the local brackish water. In order to get kosher certification, most of the vineyard’s grapes are sent to the Barkan Wine Cellars for bottling.

They return 3,000 bottles, to which the Boker Valley Vineyards Farm label is attached and sold in the restaurant. Another 900 bottles of non-kosher wine are produced at the farm itself. The price averages under $10 per bottle.

When Mr. Wiesman stands amid the dusty rows of grape vines, he has a vision. Now there is wine from the Negev; soon there will be a booming tourist trade. “This is Israel’s new wine country,” he says.

Traveling in the Negev

Beer-Sheva, a city of 200,000, is considered the gateway to the Negev. You can drive or take a bus from Tel Aviv, a couple of hours away. There is also train service, a 45-minute ride.

You can tell where the desert begins because the lush green fields and orchards that line the side of the highway gradually give way to a more arid landscape. In Beer-Sheva, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev has 18,000 undergraduates and 5,000 graduate and medical school students.

The campus has been built over time and the newer buildings are quite modern, designed by Israel’s leading architects. Tours of the campus can be arranged by calling the Visitors Unit at 972-8-646-1280 or visit the Department of Public Affairs Web page.

A 50-minute drive south of Beer-Sheva takes you to the town of Mitzpe Ramon. This is a good base from which to tour the Negev. We stayed at the Isrotel Ramon Inn.

Part of the Isrotel hotel chain, it’s a friendly family resort with comfortable rooms and terrific Israeli breakfasts and dinners.

The hotel is near the Ramon Crater, a deep canyon at the bottom of which was the ancient Nabatean trade route. There are hikes and, for the adventurous, rappelling into the canyon.

The Mitzpe Ramon Visitors Center is situated on the edge of the Ramon Crater. Models depict the geography and geology; an audio-visual display describes the formation of the Negev and its craters, the history of its settlement, and the local flora and fauna.

A rooftop observation deck has a breathtaking view of the crater. A promenade starts at the Visitors Center and runs along the crater’s edge; a “bird balcony” hangs over the crater. For information about the Mitzpe Ramon Visitors Center, call 972-8-658-8698.

Farther south, at the edge of the Avdat plateau that runs along the canyon, is the Avdat National Park. The Israeli Nature and National Parks Protection Authority oversees the park and runs a visitor center with films, displays and a restaurant.

You can take a driving/walking tour of the park that includes a tour of the ancient Roman city of Avdat at the top of the plateau. To contact the Avdat National Park, call 08-655-1511 or visit the Web site.

The Boker Valley Vineyards Farm is located in the Negev Highlands, not too far from Kibbutz Sde Boker, where Israel’s founding father, David Ben-Gurion, retired and is buried. The farm has “desert” lodges to stay in, a guest tent for outdoor entertaining, and a restaurant/bar.

Local wine and other products are sold. To contact the Boker Valley Vineyards Farm, call 972-8-657-3483, e-mail [email protected] or visit the Web site.

The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research is located on BGU’s Sde Boker campus (which BGU spells as Sde Boker).

There are three research institutes within: the French Associates Institute for Agriculture and Biotechnology of the Drylands, the Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research, and the Swiss Institute for Dryland Environmental Research.

The Blaustein Institutes are all about desert research, from engineering hardier seeds to developing sustainable water policies and encouraging eco-friendly urban planning.

Located in a cluster of modernist-looking “green” buildings, the Blaustein Institutes sponsor intensive workshops, graduate degree programs and conferences besides the research conducted by its staff. For information about the Blaustein Institutes, call 972-8-659-6710 or visit the Web site.

Sde Boker is both a BGU campus and a kibbutz town that is the site of the Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism.

Ben-Gurion’s papers are stored at the institute. Ben-Gurion and his wife, Paula, are buried side-by-side on a promontory overlooking the Ramon Canyon. For information about the Ben-Gurion Research Institute, call 972-8-659-6938 or visit the Web site.