Turkey’s Killing Fields

June 20, 2019

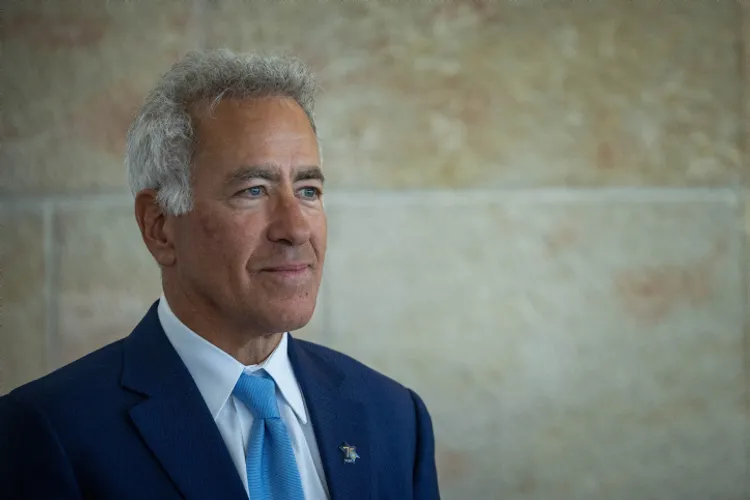

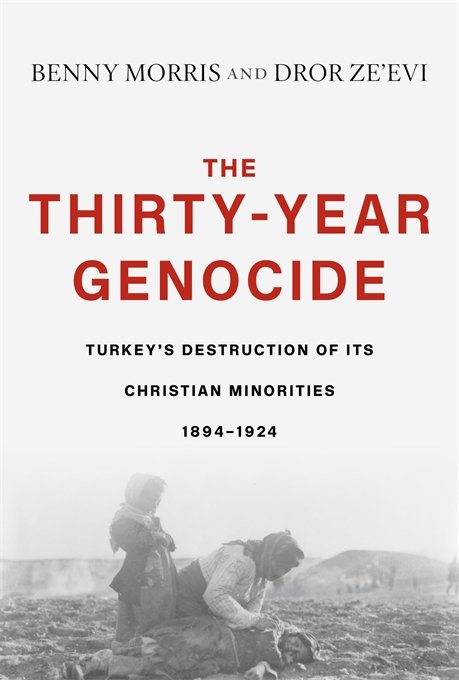

Below is an excerpt of a New York Times book review of “The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of its Christian Minorities, 1894-1924” by BGU Profs. Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi of the Department of Middle East Studies.

The New York Times — The authors are distinguished Israeli historians. Their narrative offers a subtle diagnosis of why, at particular moments over a span of three decades, Ottoman rulers and their successors unleashed torrents of suffering.

“The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of its Christian Minorities” examines three episodes: first, the massacre of perhaps 200,000 Ottoman Armenians that took place between 1894 and 1896; then the much larger deportation and slaughter of Armenians that began in 1915 and has been widely recognized as genocide; and third, the destruction or deportation of the remaining Christians (mostly Greeks) during and after the conflict of 1919-1922, which Turks call their War of Independence. The fate of Assyrian Christians, of whom 250,000 or more may have perished, is also examined, in less detail.

An impressive chapter explains the buildup to the 1894-1896 massacres. It describes the strain imposed on rural Anatolia by newcomers fleeing Russia’s march through the Caucasus, and the transformation of the Armenians from a religious minority into a political community feared by the Ottomans. This story is told with a feeling for shading and nuance.

An impressive chapter explains the buildup to the 1894-1896 massacres. It describes the strain imposed on rural Anatolia by newcomers fleeing Russia’s march through the Caucasus, and the transformation of the Armenians from a religious minority into a political community feared by the Ottomans. This story is told with a feeling for shading and nuance.

As diligent historians, Morris and Ze’evi acknowledge many differences between the three phases of history they recount. (For example, different regimes were involved: in the first case, the old guard of the empire; in the second, a shadowy clique of autocrats; in the third, a secular republic.)

But their self-imposed mission is to emphasize continuity. As they argue, the Armenian death marches of 1915-1916 are by now well documented, and their status as a genocidal crime, with one million or more victims, well established. By contrast, they feel, things that happened at the beginning and end of their chosen 30 years need to be better known, so that all the travails of the Ottoman Christians over that time can be seen as a single sequence.

Between 1894 and 1924, they write, between 1.5 million and 2.5 million Ottoman Christians perished; greater accuracy is impossible. Whatever the shifts in regime, all these killings were instigated by Muslim Turks who drew in other Muslims and invoked Islamic solidarity. As a result the Christian share of Anatolia’s population fell from 20 percent to 2 percent.

In one of their best passages, Morris and Ze’evi carefully discuss possible interpretations of the 1915-1916 bloodbath, and offer comparisons with debates about Hitler’s Holocaust. As they note, historians have disputed how far in advance the mass annihilation of Jews was dreamed up. Regarding the Armenians, they say, there is no doubt that the death marches that began in April 1915 were centrally coordinated. But there have been reasonable arguments over how long in advance they were planned, and whether it was always intended that most victims would die.

Sifting the evidence, Morris and Ze’evi conclude that the Ottoman inner circle began planning deadly mass deportations soon after a Russian victory in January 1915. However, Ottoman policy was also shaped and hardened by the battle of Van, in which Russians and Armenians fought successfully, starting in April 1915. These conclusions rest on careful analysis.

Read the full review on The New York Times>>