Robot Cuddles Fill Void When Touching Is Taboo

Robot Cuddles Fill Void When Touching Is Taboo

June 18, 2020

Medical Research, Robotics & High-Tech

The Times of Israel — As the coronavirus pandemic leaves many missing the warmth of human embrace, BGU scientists find robots can help those suffering through pain when there’s nobody to hold their hand.

As part of the study, participants exposed their skin to high temperatures. Findings indicated that with the companionship and touch of a furry robot, the subjects experienced pain less intensely.

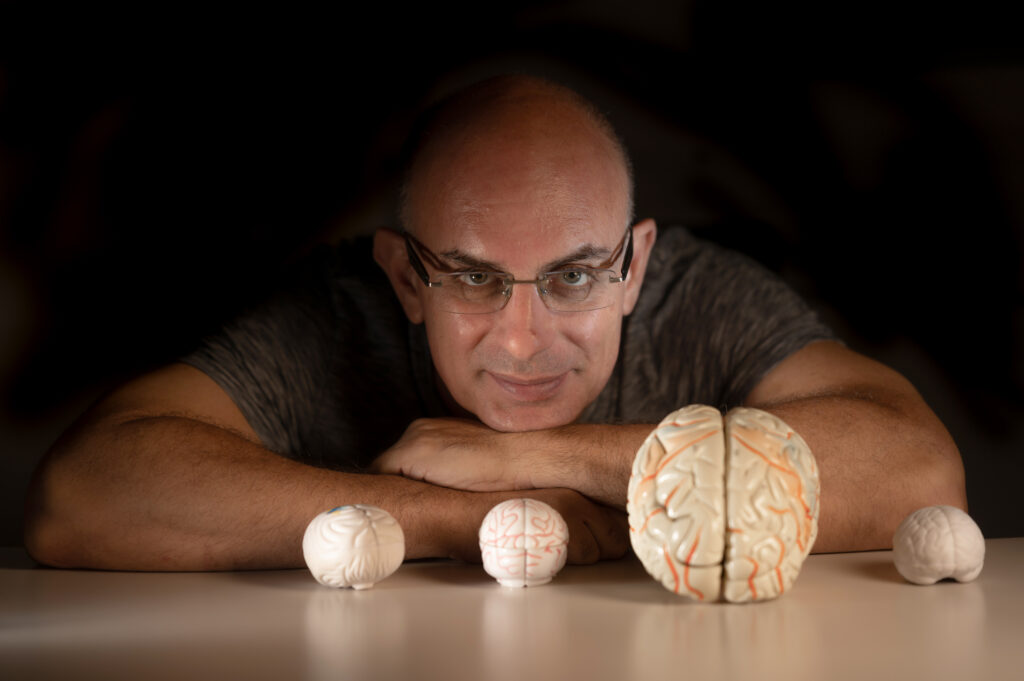

Dr. Shelly Levy-Tzedek, head of BGU’s Cognition, Aging and Rehabilitation Lab in the Department of Physical Therapy and a member of the Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience

Published in the journal Scientific Reports, this research represents “an early step in the direction of robotized pain relief,” says Dr. Shelly Levy-Tzedek, head of the Cognition, Aging and Rehabilitation Lab in BGU’s Department of Physical Therapy and a member of the University’s Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience, adding that it adds to a body of research that could make companion-robots commonplace in hospitals and for the elderly.

Human touch is known to have potential to make people feel less pain, but during social distancing restrictions, doctors, nurses, care givers, and other non-relatives who may normally offer physical comfort often won’t, notes Dr. Levy-Tzedek.

“Our research suggests that social robots can help to alleviate some of the loneliness and other feelings people have from lacking social touch and human interaction,” says Dr. Levy-Tzedek. The findings present a new contribution to the field, which has generally concentrated on children as opposed to adults.

Healthy adults took part in sessions lasting just under an hour, during which they were subjected to different levels of pain.

Some of the 83 volunteers were introduced to PARO, a Japanese-produced social robot that looks like a furry white seal. The robot makes seal-like noises and moves its head and flippers in response to being touched and spoken to.

No funding or assistance was received for the research from any robotics company.

PARO interacted with the volunteers, and asked them to perform a series of exercises that invited their touch.

As well as feeling pain less intensely, those who interacted with the robot reported higher happiness levels than the others, and were found to have lower levels of oxytocin.

While oxytocin is known as the “love hormone,” when produced outside of a relationship context, it can reflect stress, suggesting that the robot causes a drop in stress levels.

The drop in pain levels is particularly promising. “Even a short interaction with a robot can lead to reduction in pain, and this opens up possibilities for robots to deal with situations of pain, whether it’s having blood drawn or after an operation,” says Dr. Levy-Tzedek.

The findings “reveal a profound effect of human-robot social interaction on pain and emotions” and “offer new strategies for pain management and for improving well-being,” says Dr. Levy-Tzedek.