Remembering the Fallen Through the Living

Remembering the Fallen Through the Living

May 1, 2019

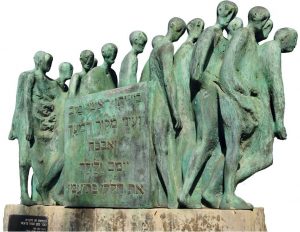

In Memory of the Death March from Dachau, by Hubertus von Pilgrim, at Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem

Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom Hashoah in Hebrew) is a national day in Israel commemorating the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust. It begins this year at sunset on May 1 and ends the following evening, according to the traditional Jewish custom of marking a day.

We’d like to commemorate this day by sharing with you an excerpt from an article in the summer 2017 issue of Impact magazine, published by Americans for Ben-Gurion University. It is titled “Israel and the Holocaust,” and features the pioneering work of Prof. Emerita Hanna Yablonka, who created the first Israel studies program at BGU and spent her academic life dedicated to researching the stories of survivors. Below, one of her students, Dr. Rachel Herzog, shares some of her work researching the physicians who were survivors and the challenges they encountered as newly arrived immigrants, straight from the terrors of World War II.

Telling the Doctors’ Story

Seven years ago, Rachel Herzog—at age 60—decided it was time to do something she’d planned for a long time: earn a Ph.D.

“The subject I was most interested in was the Holocaust,” she recalls.

She and her husband are both children of survivors. “But it was not talked about in our homes,” she says. “So I decided to focus my research on the encounter between Holocaust survivors and Israeli society. I’d worked for doctors for nearly 20 years, and decided to focus on survivor doctors because this group had not been studied. I found Hanna Yablonka to supervise me.”

Herzog spent four years on the research, searching out all the physicians who came to Israel between 1945 and 1957. “I looked at their personal history and their careers; I learned about the health of the society at the time, which was awful—a very high mortality rate. Only 15 of the doctors were still alive, so I talked to friends and families. They gave me letters, photos, diaries, and shared memories. It was very interesting and very exciting. Sometimes I cried.”

Herzog found another untold story. Like all Holocaust survivors in Israel, the doctors faced difficult times. Employers in the health system—arguing that these doctors hadn’t practiced for 10 years and that they didn’t speak Hebrew—were skeptical of their skills. Hard work, low salaries and bad accommodations confronted them. Israeli society was not prepared to accept them nor did it understand them. Yet, these physicians were badly needed. Many new immigrants suffered from chronic diseases, or were sick and disabled, requiring hospitalization and care. Israel’s uneven development had created a concentration of doctors with established practices in a few areas, and huge areas were left virtually unserved.

“Their contribution was enormous,” Herzog says. “They were the first to be sent to the villages and frontier settlements where the established doctors wouldn’t go. They were absorbed by the healthcare system and contributed a lot to its development.”

The numbers surprised her. “There were more than a thousand of these immigrant doctors. In 1952, they represented a third of all Israeli doctors, and by then many had already reached management level.” Beyond their major role in building the health care system, this group became a model for the absorption of other immigrants. “It was an amazing story,” Herzog says, “a story of strength and human victory that should be better known.”

Dr. Rachel Herzog is currently a historian and independent researcher. She works as a labor relationship counselor for the physician members of the Organization of Clalit Health Services, Israel’s chief medical provider.

To read the entire article, click here and go to page 8 >>