Cuddling A Furry Robot Makes Life Less Painful

Cuddling A Furry Robot Makes Life Less Painful

July 1, 2020

Medical Research, Robotics & High-Tech

By Evan Ackerman, an Americans for Ben-Gurion University Fromson Fellow from the 2017 Murray Fromson Journalism Fellowship

IEEE Spectrum — Everybody loves Paro. Seriously, what’s not to love about Paro, the robotic baby harp seal designed as a therapeutic tool for use in hospitals and nursing homes?

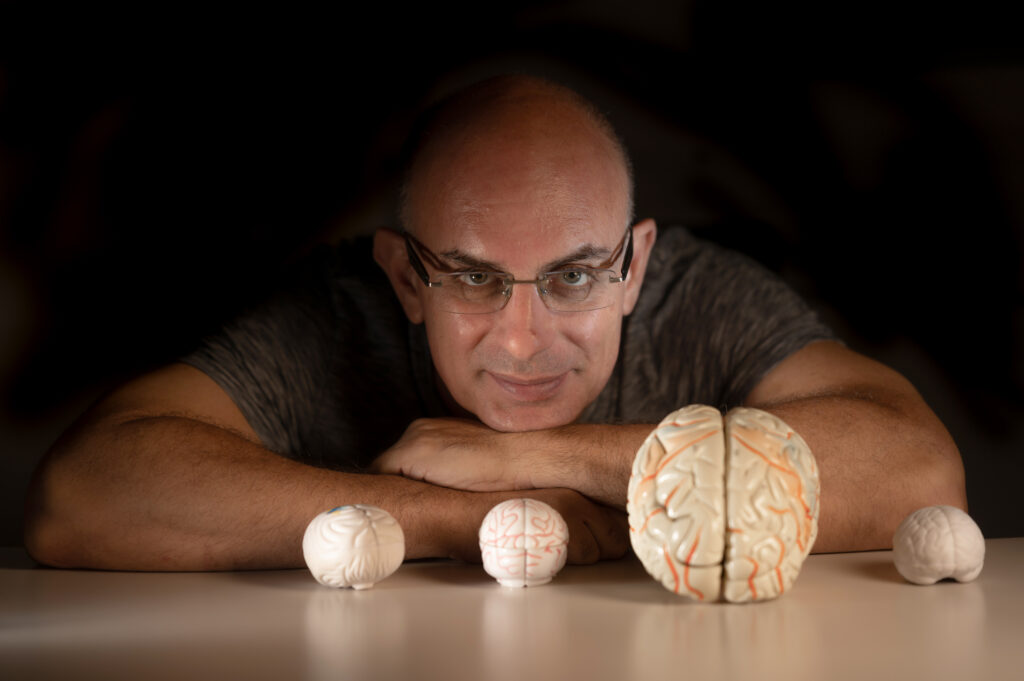

Dr. Shelly Levy-Tzedek, head of the Cognition, Aging and Rehabilitation Lab, with PARO – a baby-seal-like robot

A BGU team of researchers led by Dr. Shelly Levy-Tzedek, head of the Cognition, Aging and Rehabilitation Lab in BGU’s Department of Physical Therapy and a member of the University’s Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience, along with Nirit Geva and Florina Uzefovsky, recently published a new study measuring exactly how much Paro can help you when you’re being subjected to pain.

And how did they do that? By subjecting people to pain, and then handing them a Paro to snuggle.

Click the image below to watch a video of the experiment:

The study involved subjecting around 80 participants to a spectrum of pain sensations ranging from “mild” to “strong,” while allowing some of them to see Paro and others to touch Paro and then determining whether that mitigated the pain at all.

The pain was generated for just a few seconds by a heating plate attached to the forearm, and the participants had direct control over not just stopping it but enabling an active cooling system to remove the heat as quickly as possible.

“The feedback from participants was positive about their experience, and many of them said (unprompted) that they were willing to return for future experiments,” says Dr. Levy-Tzedek.

In addition to recording the subjective pain measurement from each participant, the researchers also took samples of oxytocin and had folks fill out a questionnaire about what they were thinking and feeling.

The primary finding of the study is that touching Paro does, in fact, reduce the perception of pain.

Participants rated their pain sensation as significantly lower when touching Paro relative to their baseline pain ratings.

Touching Paro also made people happier in general, with an intensity that was correlated with how happy those people thought Paro itself was.

What’s worth highlighting here is the importance of wanted social touch.

This same kind of pain reduction effect can be achieved when someone is holding hands with a partner, but not with a stranger, putting Paro in a curious position as a social agent.

The BGU researchers suggest that the robot is effective because “touching PARO enabled participants to form an emotional connection with it,” turning the robot into a more effective social agent than a stranger who is an actual human.

The obvious thing to think would be that cuddling Paro increases oxytocin and that’s where the decrease in perceived pain comes from, but when the BGU team measured oxytocin levels during the study, they found the opposite: Oxytocin levels decreased in people who got to touch Paro.

Dr. Levy-Tzedek thinks that this may have been because Paro significantly reduced stress, which also reduces oxytocin, and it turned out that this effect was most pronounced in participants who felt the strongest connection with Paro.

Dr. Levy-Tzedek hypothesizes that the reason we see such a strong effect of touching Paro is that there was a social connection (however superficial) that was formed with it, and that facilitated the reduction in pain perception.

Paro can be used to help manage pain and improve emotional states in young adults (a population that has not been studied in this context: you’ll see that the majority of studies with Paro look at either children or older adults mostly with dementia).

These findings are particularly relevant now, during COVID-19, when we are instructed to keep a social distance from other people, including close ones, and there is a reduction in the availability of close affective touch.

A social robot may help in this period—not as a permanent solution, but as a temporary one.

To read more, including an interview with Dr. Levy-Tzedek, visit IEEE Spectrum >>