Class War

May 6, 2009

The conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians is often framed in terms of religion or geography. But in what ways is the struggle also an economic one?

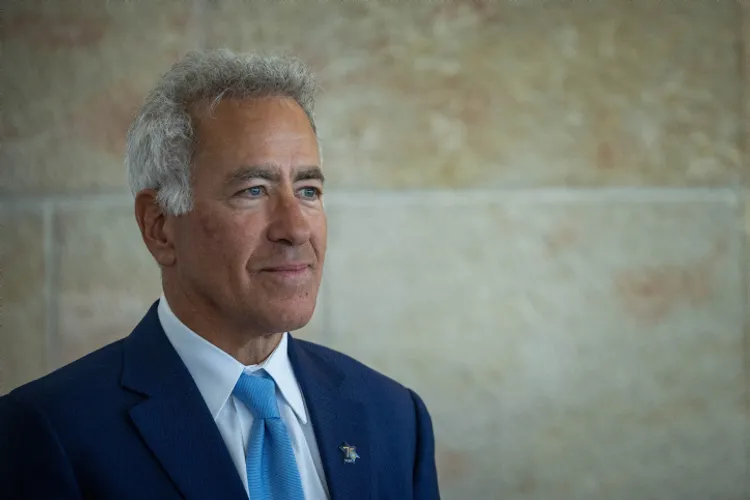

According to Guy Ben-Porat, the factors impacting the peace process in Israel have more to do with class and money than many would like to think.

Ben-Porat, a lecturer in the Department of Public Policy and Administration at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, delivered a talk at Hillel at the University of Washington on April 20 about the impact of globalization on the peace process in Israel in comparison with other conflicts around the world. His visit was sponsored by the David Project and the Legacy Heritage Fund.

“Every conflict has a political economy,” Ben-Porat explained. “There is a theory that economic growth can help mitigate conflict. But it can also drive conflict.” He believes that in Israel for the past two decades, the latter has been true.

“If economic gains are going to be helpful [for peace], they have to be constructed in such a way that they are beneficial to all,” he said. “This has not been the case for Israel.”

Ben-Porat is the author of Global Liberalism, Local Populism, in which he compares the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians to that of the Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland with regard to the effects of both nationalism and globalization.

In Northern Ireland, he explained, the peace process was helped along by the economic growth of the 1990s. Middle East experts had hopes at the time that the same would be true for Israel.

However, despite significant advances in high-tech industry and a major boost to the nation’s GDP, Israel made little lasting progress toward peace in the 1990s, and by 2000 Israel was mired in the second intifada while Northern Ireland was actively engaged in peace negotiations that would prove fruitful in the following years.

How could an economic boom have contributed to peace in one conflict, but acted as a hindrance to the other?

According to Ben-Porat, it’s not the growth of Israel’s economy that has been the problem. Rather, the trouble is that that growth has not occurred evenly throughout Israeli society.

“If you are working in Tel Aviv in the tech industry, great,” he said. “But if you live in the south and are working in a textile factory, well, that factory got shipped to Jordan. That’s the new Middle East economy.”

For working-class Palestinians, the boom has done little to enhance their quality of life. If anything, it has only served to widen the gap between themselves and their Israeli neighbors.

“In Israel, the economic prosperity was with the upper and middle Ashkenazi class, so people on the periphery were unimpressed, or even hostile,” Ben-Porat said.

“In Northern Ireland, the economic prosperity and growth was more inclusive.”

He added that while in Northern Ireland Catholics and Protestants interact with one another in a variety of different segments of society, Israelis and Palestinians, despite their close geographic proximity, do not co-mingle.

As a result, there is less need for any sort of communication or cooperation between the two groups, and therefore, less of an interest in peace among the general public.

Ben-Porat cited statistical data from the 1990s showing what percentage of Israelis supported the peace process, broken down into categories of education and income. Most of those in favor of peace were educated, upper-middle class professionals.

“Business people see peace as being necessary for being part of the world economy,” he said.

That’s a cynical way of looking at the situation, Ben-Porat admits, but it’s not inaccurate.

“Palestinians and Israelis have never met each other as equals, and this had not changed throughout the peace process. The peace process has brought some elites together, but for the average Israelis and Palestinians, the only way they meet is if one is the employee of the other, or at military checkpoints.”

He was quick to add that there are many factors beyond the economy that must come into play for a peace process to be successful.

“Israel is stuck in many ways, not just in this,” he said. “I think the two sides [have been] talking to themselves, not to each other, for a long time.”

Consistent, dedicated communication is key to bringing about peace, he said, adding it often takes outside help to get two sides seriously talking about peace. He said he is hopeful that the Obama administration will take on that role. “Carter did that in 1978 between Egypt and Israel,” he said.

“This is a more complex case. Clinton came pretty close. The Bush administration has done extreme damage to the process and I’m hoping that this administration will make things better, but I don’t see hope from within.”

Of course, for peace talks to work, Ben-Porat believes Israel must also commit to creating a more socially and economically just society, since a conflict in which the two sides never meet as equals is doomed to continue for decades to come.

“In a lot of places, in Israeli circles, peace is thought of as the end of violence. But that by itself is not peace,” he said.

“Peace is also about justice, and you can’t have one without the other. Justice and the end of violence will have to go together. But Israel is stuck in a very rigid class position, and dismantling this is required for peace.”

JT News is the voice of Jewish Washington.